Der Krieg ist das Gebiet der Ungewißheit: drei Vierteile derjenigen Dinge, worauf das Handeln in Kriege gebaut wird, liegen im Nebel einer mehr oder weniger großen Ungewißheit.

War is the realm of uncertainty: three quarters of exactly those things upon which action in war is built, lie in the cloud of more or less uncertainty.

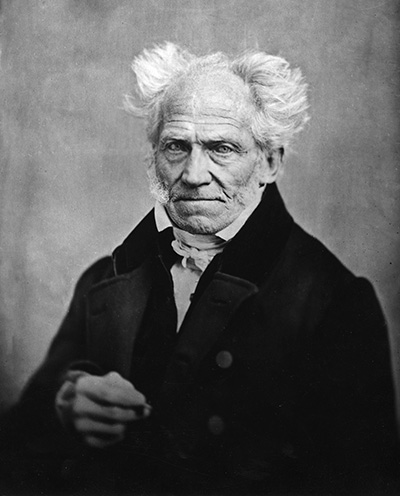

Somehow, Arthur Schopenhauer was not included in the canon of Western philosphy I was exposed to in my younger days. I became interested in him a little while ago as I learned that he was a favorite of Einstein, who was hardly a touchy-feely butterfly.

Schopenhauer started from the work of Kant, who commented that our minds are not mirrors, but containers. This already is far from the view espoused by Plato, that what we experience in our daily lives are just shadows of ideal real things – though Schopenhauer himself frequently comments about how his own views align with those of Plato. Einstein's relativity was a little bit approachable by our minds, but its general form and relation to quantum mechanics are not intuitable, rather mathematical models with implications and results we can only indirectly and partially observe.

The most original aspect of Schopenhauer's philosphy is arguably the primacy it gives to will over mind. The latter was developed, he posits, as an adjunct to the former in its struggle to emerge from and struggle with with other forces amid the chaos. I tend to agree.

Schopenhauer is as bad as a writer as he is remarkable as a philosopher. This is the more curious because his mother was a writer of some popularity. He is wordy, with sentences often half a page long and paragraphs a few pages. He is at times overblown, as when he makes the comparative merits of various art forms almost a matter of algebraic demonstration. – But self-confidence is as necessary for a metaphysician as it is for a tightrope-walker or politician.

I've completed the first volume. In a while, I expect I'll pick up the second.

– So sind die Menschen, und es wäre unbillig ihnen übel zu nehmen, daß sie so sind. Die Nachtigall singt, der Rabe krächzt, und er müßte kein Rabe sein, wenn er nicht dächte, daß er gut krächze: ja, er hat noch recht, wenn er denkt, die Nachtigall krächze nicht gut. Es is wahr, dann geht er zu weit, wenn er über die Nachtigall spöttet wie er: aber sie würde eben so unrecht haben, wenn er über ihn lachte, daß er nicht singe wie sie; singt er nicht, so krâchzt er doch gut, and das is für ihn genug.

– That is human nature, and it would not be reasonable to hold it against people that they are humans. The nightingale sings, the raven croaks, and he would not be a raven if he did not think that he croaked well. Furthermore, he would be quite right to think that the nightingale did not croak well. That is true, but he would be going too far if he then mocked the nightingale; but she would be just as wrong if she made fun of hinn because he did not sing as well as she did. Even if he doesn't sing, he croaks well, and that is enough for him.

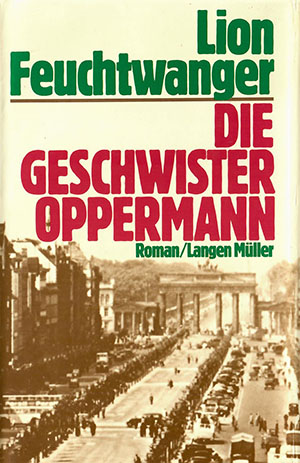

I have long been intrigued with the question of what life was like for ordinary Germans during the time of Hitler. I have long searched for reading on this topic, without success. Only recently have I run across citations of the work of Lion Feuchtwanger, who was a Jewish German writer of some prominence in the early days of Naziism. His first-hand perspective fascinated me. It is the view that I've wished for and coveted. I don't quite know why it took me so long to find it, other than perhaps that I had been looking in history and journalism rather than literature.

It turns out that I had incorrect impressions of what it was like. I had imagined that ordinary Germans had little idea of the atrocities of Naziism, which was sanitized and screened from view. It is correct that few knew of the scale and deliberateness of the genocide, but hatred and episodic violence were overt. In the earlier part of the Reich, local cells and party groups shared an ideology but had not yet coalesced into an organized and coherent whole.

Is is like the ultranationalism of today? – Yes.

Der grüne Heinrich, Wikipedia observes, "stands with Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and Adalbert Stifter's Der Nachsommer as one of the three most important examples of a Bildungsroman." The Bildungsroman, or novel of growth and development, is a genre very close to my heart, and the two other works cited are among my all-time favorites. (They are both famously, or infamously, long, and so is Heinrich.)

Heinrich is, in the words of Alice in Wonderland, "a book without pictures or conversations," not light reading. It is full of abstract ideas and complex expressions, with a lot of vocabulary that is beyond that of my dictionary.

Curiously, it is very like the early books of Rousseau's Confessions, another book I am reading, in finding significance in the vagaries and experiments of early childhood. I found myself feeling strongly empathetic with Heinrich as, at an early point in his painting work, enthused after reading a theoretical treatise on nature and art, he set out to draw a tree, with feeble results that his family and friends laughed at. I wished that I could have been there to tell him, Heinrich, trees are very hard to draw: they have a lot of leaves, and to get good effect, you need to draw around the leaves and limbs you wish to show off, because the white highlights that you haven't touched will be what will convince the eye. It's a bunch of work, even on the best of days.

More than halfway through, I am still feeling fascinated by Heinrich's story. It is a true portrait of the artist as a young man. He is alternately deeply likable and human, and socially inept and unrealistic about practical life. His failures are those of youth and inexperience, so lead us toward sympathy rather than dislike. This is the less surprising because his father died when he was young, leaving him in the hands of his mother. As he remarks of her on his leaving home,

Da sie aber die Welt nicht kannte, noch die Tätigkeiten und Lebensarten, denen ich entgegenging, und doch wohl fühlte, daß etwas nicht richtig sei in meinen Geschichten und Hoffnungen, ohne daß sie nachweisen konnte, worin es lag, so beschränkte sie sich schließlich auf den kurzen Zuspruch, ich solle Gott nicht vergessen.

Since she didn't kow the world or the activities or modes of life into which I was going, yet still felt that something wasn't quite right with my stories and hopes, without quite knowing where it was, so she confined herself to the brief observation that I should never forget God.

At the end: Wow! It does deserve being ranked with Wilhelm Meister and Der Nachsommer. Its spirit is amazingly like that of my own coming of age, though of course not in all incidental details. I rate it very highly. It is certainly not a "light read," being long, very internal, and written in complex language. (It seems to have a lot of Swiss usages that my more classical German can't quite follow.) It took me quite a while to get through it, but it was more than worth it.

Soll und haben was very widely read in Germany in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is traditional and nationalistic, extolling middle class and German values, deprecating Poland, other Slavic countries, and Jews.

I read books that have been very widely read, and books presenting beliefs that I don't particularly agree with. The Koran is one example. This is another. I've worked for quite a while to understand the factors leading to Nazism, Germany's push for Lebensraum, the background to World War II, and the Holocaust. I expected that this work would shed light on the mood when that era began. It did, a little, but not nearly as much as one can gain simply from observing the 2016 Presidential election campaigns. Yes, the villain is Jewish – but that much is true of The Merchant of Venice, which is accepted high school reading. Yes, the Poles misbehaved, but not particularly more so than opposition peoples in many other stories.

In the end, I felt that these volumes fairly rank as a neglected classic. The hero reflects the society around him, with its strong human values of behavior in an era of upheaval. He grows over the course of the story, after what is a youthful failure of judgment rather than an act of ill intent or particular harm to those around him. It's not hard to understand that its two volumes and 979 pages don't make for a "good read," and apparent that the social particulars are dated. Still, it was quite good, a bit after the mold of War and Peace, though not quite of that rank.

Curiously, it was not easy finding a copy. After some other efforts, a small seller working through Amazon provided a very serviceable edition a hundred years old. It was printed in the old German Fraktur script, which was interesting – a small barrier, but one worth crossing, in the scheme of things.

Der Nachsommer has been a major reading event for me, the book most affecting me since I read Howard Gardner’s Frames of Mind. These are books that not only offer insights and enjoyment, but have an effect on my life.

Der Nachsommer was received with considerable controversy. It is cited as one of the major novels of the 19th century. Nietzsche ranked it with Goethe’s work. It was also criticized for its excessive length, its tendency to langweilen – a fine German verb meaning to discuss trivialities “a long while.” Stifter’s contemporary Christian Friederich Hebbel famously offered the crown of Poland to anyone who could finish it. It is certainly lengthy, but I loved it.

It is often described as a Bildungsroman, a story of an individual’s growth and development, which it is. (I am very fond of this genre, with little patience for characters, like Stendahl’s Julian Sorel, who create and prolong their own misery, and the misery of people around them, through obstinate refusal to use their heads.) More than that, it is a work of utopian realism, describing in a very detailed and concrete fashion how life is most beautifully lived. Its principal character, well guided by an unnamed mentor, develops a love of nature and the arts, with little distinction between a prized specimen of marble and a painting – they both reward extended viewing. There is no conflict in the story. The closest any event comes to that is a mild suggestion about how a drawing in progress could be improved. Rather, the course of development is steady and progressive.

The mentor, who is unnamed for nearly all of the story, turns out to be a noted public figure in retirement – hence the title Der Nachsommer, or Indian Summer. He encourages the young narrator in a love marriage that he was denied during his own youth. In the end, the mentor defines the important things of life as first family, then the appreciation and creation of beauty. This is particularly poignant for me since, while I agree entirely, I have no close family left.

Excerpts follow.

… sagte mein Vater, der Mensch sei nicht zuerst den menschlichen Geschlecht wegen da, sondern seiner selbst willen. Und wenn jeder seiner selbst willen auf die beste Art da sei, so sei er auch für die menschliche Gesellschaft.

…

As ich den letzten Lehrer verlor, der mich in Sprachen unterrichtet hatte, als ich in denjenigen wissenschaftlichen Zweigen, in welchen man einen längeren Unterricht für nötig gehalten hatte, weil sie schweriger oder wichtiger waren, solchen Fortschritte gemacht hatte, daß man ein Lehrer nicht mehr für notwendig erarchtete, enstand die Frage, wie es in Bezug auf meine erwählte wissenschaftliche Laufbahn zu halten sei, ob man da einen gewissen Plan entwerfen und zu dessen Ausführung Lehrer annehmen sollte.

… my father said that man is not there in the first place for the sake of mankind, but for himself. And if each person is there for himself in the best possible way, so is he for mankind.

…

As I lost the last teacher, who had instructed me in speech, as I made such progress in the scholarly branches in which longer instruction is considered necessary, since they are harder or weightier, in which an instructor is no longer considered necessary, the question arose, how these stood in relation to my chose life course of scholarship, whether one needed to make a determinate plan, for which instructors should be taken on.

I liked this quite well from its first pages, and it grew on me steadily as I went along. The story begins with a boy who cadges a Dutch copy of Euclid from his uncle, who thinks the boy will be able to do nothing with it because it is in a foreign language. From a tattered Dutch grammar, the boy soon learns enough Dutch to understand it. The father sends the boy to work carting clay for the dikes, thinking that will rid him of his intellectual affectations and daydreams, but the boy studies the geometry of the dikes and makes models of how they could be built better.

The people and setting of the Dutch dikes are elemental and primal, very compelling. The work of its main character to fortify the protective structures is both thoughtful and passionate, but not accepted by the community, who mistrust new ways of doing things. I certainly will look at other work of this author, although Der Schimmelreiter is generally considered his masterpiece.

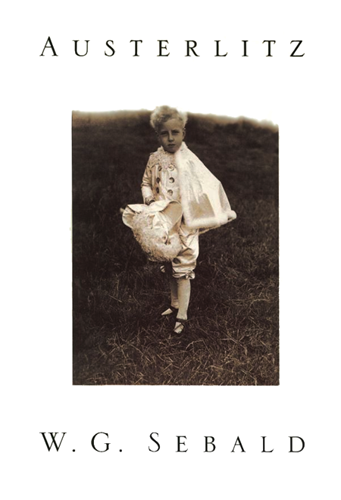

Austerlitz has received a number of awards. It is a discursive story, written without paragraphs, often in very long sentences, with frequent images that may be poignant or stark.

The critics and reviewers usually focus on Austerlitz’s unearthing of the horrors of Nazi Germany, which are ignored or buried in present life. The story does include that. I think that, more than that, it reflects the curiosity of Austerlitz about all kinds of phenomena that he runs across, and about his intense focus on these. Sometimes his focus is on his own story, sometimes on a variety of moths.

The wandering structure, without breaks, calls for special attention by the reader. That may be a good thing. I liked it a lot. I certainly would recommend it to those who might fancy such an approach.

"Es ist besser, das geringste Ding von der Welt zu tun, als eine halbe Stunde für gering halten."

"It is better to do the most trivial thing in the world than to consider half an hour as trivial."Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre

© 2025 Paul Nordberg