Hogg's picture is much like Bob Dylan's:

The corbie crows came a’ an’ sat down round about him, an’ they poukit their black sooty wings, an’ spread them out to the breeze to cool; and Robin heard ae crow speaking, an’ another answering him; and the tane said to the tither, “Where will the ravens find a prey the night?” “On the lean crazy souls o’ Auchtermuchty,” quo the tither. “I fear they will be o‘er well wrappit up in the warm linnens o‘ faith, and clouted wi‘ the dirty duds o‘ repentance, for us to make a meal o‘,” quo the first.

Oh my name it ain’t nothin’

My age it means less

The country I come from

Is called the Midwest

I was taught and brought up there

The laws to abide

And that land that I live in

Has God on its side.

Selma Lagerlöf was the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. From a first encounter, I find that very well deserved.

Her work is quite understated. It is difficult to classify, perhaps a first sign of originality in its approach. Mårbacka is somewhat of a personal and community memoir. It is made up of many vignettes, a few pages each, of personal experiences and lore from a grandmother's stories. Each episode is brief and intense, perhaps without obvious connection to the one before. Yet the totality paints a coherent picture, in a way that feels almost magically vibrant, consistent and convincing.

I wish, abstractly, that I could read this in its original language. Some years ago I started off to learn a bit of Swedish, but soon realized that any fluency would take a number of years. At this point, I imagine that what's lost in translation is much less than I would lose in poor comprehension of the original. I am very glad that I decided to forge ahead with the English version.

I enjoyed picking up this classic quite a bit. I have long been aware of and fascinated by Popper's insight that constructing successful theories is a process of falsification of opposing theories. As someone (I don't remember who) remarked, scientists don't try to prove things, they try to disprove them. Reading the text raises provokative ties to the complexity and scope of beliefs.

This is one of the very, very few times that I have read a book successfully, by my criteria, without finishing it. Toward the end, it moved into a discussion of quantum theory, which I would love to understand better. Alas, the promise to stay away from mathematics was very poorly kept, and it would have taken more than a casual commitment to learn the algebra. It also, at an early point, began to talk about how we cannot learn about things without changing them – for instance, shooting a photon at a subatomic particle. That, others have said, is a fundamental misunderstanding of the indeterminacy Heisenberg particularized. Perhaps there is no good easy way to understand the concepts involved. As one reference has it,

Quantum mechanics is, at least at first glance and at least in part, a mathematical machine for predicting the behaviors of microscopic particles — or, at least, of the measuring instruments we use to explore those behaviors — and in that capacity, it is spectacularly successful: in terms of power and precision, head and shoulders above any theory we have ever had. Mathematically, the theory is well understood; we know what its parts are, how they are put together, and why, in the mechanical sense (i.e., in a sense that can be answered by describing the internal grinding of gear against gear), the whole thing performs the way it does, how the information that gets fed in at one end is converted into what comes out the other. The question of what kind of a world it describes, however, is controversial; there is very little agreement, among physicists and among philosophers, about what the world is like according to quantum mechanics.

Barack Obama liked this book. So did I. It is within the epic tradition, though at a small scale. It is refreshing that it is not about battles, like the Iliad, but about cooperation, ideals, unity, family, and perseverance. That freshness makes up for a bit of a shortage in language.

I am prompted to pick this up again after listening to Handel's oratorio Samson, after text from Milton's Samson agonistes. The libretto is strikingly poetic and insightful in comparison with the usual trite fare. The characters have good insights into their own plights and foibles, and the language is flexible and creative.

At the outset, Milton is at pains to defend and propound his use of blank verse and flexible phrasing, where a sentence or a clause runs across line breaks. I agree with him. Singsong ta-DUM, ta-dum, ta-RUM rhythms sound more like a galloping horse or a dripping faucet than revealing dialogue. As T.S. Eliot noted, Milton's long and complex periods make for a rich sound that has few rivals.

Beyond the sound and imagery, Milton's poetry aims "to justify the ways of God to man," with characters, psychology and reasoning that are far beyond the usual. His description of Satan is often cited as giving a credible personality to that character. After the fall, the archangel Michael discusses with Adam such deep theological questions as why an already perfect God could find added satisfaction in man's adulation.

I find myself preoccupied by one absent ingredient in the tale, which is an explanation of what was evil in the original sin. Of course, one would hardly expect secular humanism in this time and place. Still, Eve, who was the first to eat the forbidden fruit, seems to have done little worse than falling for a huckster's glib line. Which of us hasn't at some time? Is it a moral failing if, not having run across talking snakes before, we don't have the street smarts to discount their talk? – Eve has the partial excuse of being of the weaker gender. Adam's fault is compounded by its deliberate nature, his acknowledgment and understanding of transgression while electing to accompany Eve. Sin is evil, apparently, because God said so, and beyond that Adam is not to attempt to understand. This leaves acceptance of hierarchy as the fundamental principle of morality. And so, I guess, it was, heavenly hierarchy and earthly hierarchy.

Corporations have lives that are well described by the principles of Darwin. They have an instinct for self-preservation, even after the initial need that gave rise to them has been met. They grow, and compete with others their size – but at other times they herd with them. They need food, and to survive over the long term must develop behaviors like sexual selection, with the peculiar twist that the fancies they must meet – or create – are those of their customers, who feed them.

Galbraith's view is that the modern technostructure goes beyond the corporation, so that business, government and educational institutions share an interest in preservation of the planning system. There's no doubt much truth in what he says. Apple's yearly release of new iPhone models, and the growth of subscription plans for software, fit well with his descriptions.

It is a delight reading this work and following how the author approaches his subject. He comes at it from many different sides, rather than riding a single notion like a hobby-horse, from one angle. He is continually saying, there is another way we may look at this. He readily admits his puzzlement with the remark that in a given area, our ignorance is profound, and devotes careful attention to arguments against his theory. He is a naturally curious person.

Beyond being the proponent of a radical idea of immense power, he is a writer who creates much interest and pleasure. I am surprised that I have not read any of his writing earlier, but very glad to have opened it now. It has been a delight to follow his mind at work.

This is an early view of infidelity from a woman's viewpoint, considered shocking in its time. Somehow I have never read Kate Chopin until now, perhaps because in my earlier days such writing was considered unsuitable. Now, it approaches the status of a classic.

Kate Chopin has an impressive command of the craft of writing. Each phrase counts and builds. She is aware of the broad moral plane around her central character's intensely personal meditations and caprices, in welcome contrast to another book I read not long ago. There is no solution to the conflicts, either in the classical virtue of La Princesse de Clèves or in the tempestuous passion of Die Leiden des jungen Werthers. The conflict is continuing, even if the life of Chopin's central character ends.

I find myself wanting to read more of Kate Chopin's work, though her output was relatively slim.

I really enjoyed Caro's volume on Lyndon Johnson's vice-presidency and early presidency, The Passage of Power. I am picking up things in reverse order, going back to Johnson's time in the Senate. Caro is as interested in the context as much as in the subject of his biography. His discussion of the Senate and its slowness reminds me of early civics schoollessons. It was by design of the Founding Fathers that the Senate structure did not lend itself to rapid change of any kind, and the reading helps me understand that present-day obstructiveness is hardly anything new there. Caro is a master biographer, digging deeply into the contradictions of the man Lyndon Johnson and providing a deep view of how his subject fit into his milieu.

I am very much looking forward to the the planned final volume of the five-part series.

I haven't given much attention to philosophy for a few decades. I suppose I generally tend to believe increasingly that our minds are wired in curious ways that are mostly effective for daily life, but not necessarily good at objective, logical views of larger realities.

Nozick draws on many sources of understanding and knowledge, notably empirical ones. He remarks, there are no interesting or important metaphysical necessities. (I would generally go along with that view.) He makes much of general relativity, quantum mechanics, and evolution. For example, he discusses ethics as principles that were selected for in evolution as cooperation for mutual benefit. He notes the role of consciousness in evaluating and assimilating experiences from different viewpoints, for instance the feel of heat from fire with its appearance. As the title of the work suggests, he feels that the "reality" of things of various sorts is demonstrated when their presence is invariant when viewed from different perspectives or by different persons. This is an insight that I find useful in everyday life. For example, I sometimes find piano keys by feeling how far my hand has moved, sometimes by feeling them with my fingertips, sometims by imagining how the keyboard looks. Sometimes my fingers just seem to learn how to find the desired keys without any conscious effort.

The discussions of the implications of relativity and quantum mechanics are provocative. It indeed turns our usual ideas of logic upsidedown if indeed whether something happens before or after something else depends on the placement of the observers. I am not sure how far phenomena at the far end of tininess or hugeness are material for our understanding of things we are more used to daling with and thinking of.

Nozick offers very provokative thought and reading. It's easy to see why he was Chair of Philosophy at Harvard.

Gawande understands very well that death is part of life, and that fighting to prevent it will not only become futile at a certain point, but will create unnecessary pain. Refusing to think about death will only add to the terror of the notion of it.

MODERN SCIENTIFIC CAPABILITY has profoundly altered the course of human life. People live longer and better than at any other time in history. But scientific advances have turned the processes of aging and dying into medical experiences, matters to be managed by health care professionals And we in the medical world have proved alarmingly unprepared for it.

I highly recommend this book.

I picked this up from Project Gutenburg as light bedtime reading. It is that, with short chapters and a very direct appeal, but it is also very good.

The story proceeds on many different levels. The descriptions of daily life on the Great Plains are among the richest I've seen. People often didn't have very much at all, and often had experienced upheavals in their lives that drove them from Europe. Some were enterprising, some were stoic, others became lost and withdrawn. Some were heroic. Its characters change and interact with each other. Willa Cather empathizes with her characters in their rapturous moments and sad ones. A man who misled Ántonia is the closest thing there is to a “bad” person, but he is present only offstage and as a step from one place to another in her life, an event that influences its course just as a snowstorm influences her life.

At the same time as the characters were growing older, frontier was evolving into cultivated areas with wandering ways through them, and then the cultivated areas sprouted towns and the wandering ways gave way to straight roads. People whose lives were closely knit in very small communities go their various ways. Throughout the character of the land is always close, shaping people’s lives as much as other people around them do.

Willa Cather considered it her best book. I think it is a very good one.

Curiously, though my mother liked Cather, she never mentioned this book or had a copy of it in her library. I wonder if she knew of it. She clearly would have liked it.

I enjoyed this well-written little book. Gilligan argues, fairly persuasively, that while men look for abstract general principles, women more often find meaning and importance in the relationships they have to particular other people around them. For instance, she observed boys and girls playing games. If a dispute about rules arose in a game boys were playing, they would argue out the rules. Often boys who weren’t taking part in the game would join into the arguments about the game. If a dispute about rules arose in a game girls were playing, they would just stop playing the game. – After all, the purpose of the game was to be enjoyment for the group, and if abstract rules were keeping people from enjoying themselves and hurting the relationships, why hang onto the rules?

I wouldn't take this view too far, but it does ring true. I hear it borne out continually in random snippets of conversations of people around me.

Alexander Thayer's exhaustive 19th-century Life of Beethoven is generally considered the definitive Life of Beethoven and a model of objective biography. Elliot Forbes, whom I met and saw a few times, produced the definitive 20th-century edition with extensive revisions and new material. The work is a model of objective, carefully researched biography. It does not speculate about what Beethoven was thinking or attempt to interpret his music. By concentrating exclusively on primary source materials, it has an inadvertent but unavoidable focus on some aspects of his life, notably his relationships with patrons and publishers – at least as reflected in the surviving correspondence.

Beethoven was by all accounts a strange person. One report notes that he would walk out of a restaurant without thinking of paying for his meal. He could do that, and no one would call him back. After all, he was Beethoven. That was good enough for the restauranteurs, and it's good enough for me.

I learned a lot about the man from this biography. At over a thousand pages, it took a while to get through.

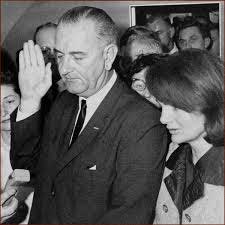

This is the fourth of Caro’s planned five volumes on The Years of Lyndon Johnson. This one covers the period of Johnson’s Vice Presidency and early Presidency. It is meticulously and exhaustively researched, with a balanced but not cold or dry approach.

At the time, I had no liking or even tolerance for Johnson. He seemed crude after the Camelot of the Kennedy years, and his term was overshadowed by the Vietnam War. Now, I’m not so sure. For all of Kennedy’s inspirational abilities, he didn’t get a lot done in Washington. Johnson did, and Vietnam was something Johnson inherited, just as Barack Obama inherited Guantanamo and Afghanistan. There was no elegant escape possible.

I would very much recommend this book to those interested in the subject and times. I certainly will want to read the last volume of Caro’s series.

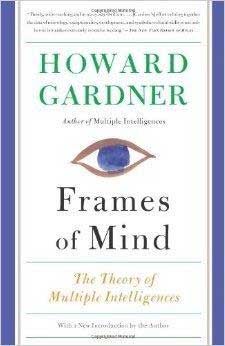

The notion that there is a general, unitary intelligence, such as IQ tests set out to measure, has been a controversial one. Howard Gardner has attracted much notice for his belief that there are multiple kinds of intelligence. It is not simply a question of the truism that different people are good at different things, which no one would dispute. Gardner proposes specific criteria that an “intelligence” should meet and identifies eight abilities that meet the criteria. His discussion is often discursive, depending on the topic at hand, and entertaining for that reason. For instance, in discussing music, he cites examples of recognized composers to suggest that musical facility tends to be developed precociously. For other skills, he will note how injuries to a certain part of the brain will leave a person’s functioning intact at high levels, except for a specific deficit in one area.

Gardner has believed that birth is not destiny for the various intelligences, that a person may develop abilities in fallow areas (within some limits, of course). I have found that to be true, and I believe that reading his book has helped me realize that I can draw things out of myself that I have not seen before. The enabling realization is that to do this, I need to use approaches that are different from the ones that have worked for other things.

The book is very readable, though certainly not at the popular culture level. I highly recommend it.

"I resent violence or intolerance in any shape or form. It never reaches anything or stops anything. A revolution must come on the due instalments plan. It's a patent absurdity on the face of it to hate people because they live around the corner and speak another vernacular, so to speak."

Leopold Bloom in James Joyce, Ulysses

"Care is nothing if not active."

"Science students accept theories on the authority of teacher and text, not because of evidence."

– Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions© 2026 Paul Nordberg