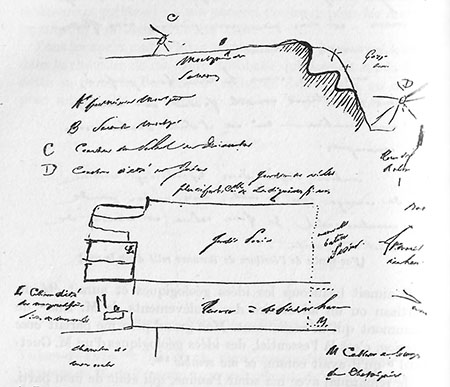

The Vie de Henry Brulard by Marie-Henri Beyle, usually known by his pen name of Stendhal, is a curious unfinished work, an autobiography.

Stenhal aims to describe events, places, and persons as he finds them in his memory, not as they have been described to him. Often the events and conversations are sited in particular spaces, which he illustrates in rough form. Here, a discussion of his grandfather and his grandfather's political views is associated with a terrace overlooking a mountain.

… je ne prétends nullement écrire une histoire, mais tout simplement note mes souvenirs afin de devine quel homme j'ai été :bête ou spirituel, peureux ou courageux. C'est la rêponse au grand mot : Gnothi sauton.

I do not intend at all to write a story, but simply to set down my own memories, in order to understand what kind of man I have been – timid or courageous. It is the response to the great imperative: γνθειν σ'αυτον.

Stendhal did not get along with his father. He writes, « J'observais, avec remords, que je n'avais pas pour lui une goutte de tendresse ni d'affection » – "I remarked, with remorse, that I did not have a shred of tenderness or affection for him." My own case is the same. Despite much effort and search, I cannot recall a single happy moment or event of my life with my father, though we were alive many decades together. Probably there were such moments, but they were swallowed by the strongly negativity of the relationship overall.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his Confessions is noted for having passed beyond hagiography in biography and onto recounting of details of life, flattering and unflattering. Stendhal moved intriguingly beyond that into details and particulars of what of his life was in his mind at the time he was writing. I have found it raising fascinating questions about memory. I tend to view it as many others do, as an unfinished masterpiece, though I have found other works by Stendhal unrewarding. Perhaps I will try again with Le rouge et le noir.

These are the reflections of a man of long travels and experience but few illusions:

Il n'y a plus rien à faire : la civilisation n'est plus cette fleur fragile qu'on préservait, qu'on développait à grand-peine dans quelques coins abrités d'un terroir riche en espèces rustiques, menaçantes sans doubte par leur vivacité, mais qui permettaient aussi de varier et de revigorer les semis. L'humanité s'installe dans la monoculture; elle s'apprête a produire la civilisation en masse, comme la betterave. Son ordinaire ne comportera plus que ce plat.

There is nothing left to do for it: civilization is no longer the fragile flower that we have sheltered, we have cultivated with great pain in certain protected nooks of a land rich in rustic species, no doubt menancing because of their vitality, but allowing at the same time variation and reinvigoration of their seeds. Humanity has constructed a monoculture, lending itself to mass production of civilization, as of beets. Its menu allows no choice other than this recipe.

Et voici, devant moi, le circle infranchissable : moins le cultures humaines étaient en mesure de communiquer entre elles et donc de se corrompre par leur contact, moins aussi leurs émissaires respectifs étaient capables de percevoir la richesse et la signification de cette diversité.

And so, before me, was the unsurmountable difficulty: the less human cultures were able to communicate with and so to corrupt each other by their contacts, the less their respective emissaries were able to realize the richness and the meaning of their diversity.

I have read this series a few times in my life, first in English and then in French. It became one of my mother's favorites as well. It's been a while, and it's time again.

Du côté de chez Swann

On the current go-around, Proust is even better. He understands well the story-teller's craft.

La trouvaille du romancier a été d'avoir l'idée de remplacer ces parties impénétrables a l'âme par une quantité égale de parties immatérielles, c’est-a-dire que notre âme peut s'assimiler. Qu’importe des lors que les actions, les emotions de ces êtres d’un nouveau genre nous apparaissent comme vraies, puisque nous les avons faites nôtres, puisque c'est en nous qu’elles se produisent, qu'elles tiennent sous leur dependance, tandis que nous tournons fiévreusement les pages du livre, la rapidité de notre respiration et l'intensité de notre regard? Et une fois que le romancier nous a mis dans cet état, ou comme clans tous les états purement intérieurs toute emotion est décuplée, où son livre va nous troubler à la façon d'un rêve mais d’un rêve plus clair que ceux que nous avons en dormant et dont le souvenir durera davantage, alors, voici qu’il déchaine en nous pendant une heure tous les bonheurs et tous les malheurs possibles dont nous mettrions dans la vie des années a connaitre quelques-uns, et dont les plus intenses ne nous seraient jamais révélés parce que la lenteur avec laquelle ils se produisent nous en ôte la perception; ainsi notre coeur change, dans la vie, et c'est la pire douleur; mais nous ne la connaissons que dans la lecture, en imagination : dans la réalité il change, comme certains phénomènes de la nature se produisent, assez lentement pour que, si nous pouvons constater successivement chacun de ses états différents, en revanche, la sensation même du changement nous soit épargnée.

Much of this first book is about love. Swann's love for Odette, who is far beneath him socially, is blind, leading him to jealousy and unavailing efforts for posession. Blindness is the proverbial nature of love. The narrator's crush on the couple's later daughter Gilberte is no less blind and one-sided.

Mais la beauté de cette pierre, e la beauté aussi de ces pages de Bergotte que j’étais heureux d'associer a l'idée de mon amour pour Gilbert, comme si clans les moments ou celui-ci ne m’apparaissait plus que comme un néant, elles lui donnaient une sorte de consistance, je m'apercevais qu’elles étaient antérieures à cet amour, qu'elles ne lui ressemblaient pas, que leurs elements avaient été fixes par le talent ou par les lois minéralogiques avant que Gilberte ne me connut, que rien clans le livre ni clans la pierre n'eut été autre si Gilberte ne m'avait pas aimé, et que rien par consequent ne m'autorisait a lire en eux un message de bonheur.

À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs

Proust is far beyond a mere diarist or fact-recounter. He always has something to say, with an unusual ability to see into himself and other people. He is fascinated with how we change over time, which is indeed the major theme of his work.

J'étais pourtant jeune encore tout de même puisque j'avais pu lui en écrire un par lequel j'espérais, en lui disant les rêves solitaires de ma tendresse, en éveiller de pareil en elle. La tristesse des hommes qui ont vieilli c'est de ne pas même songer à écrire des telles lettres dont ils ont appris l'inefficacité.

I was still young, however, since I could write one by which I hoped, in expressing the solitary dreams of my tenderness, awake a similar emotion in her. The sadness of men who have grown old is to not even dream of writing such letters, of which they have learned the inefficacy.

He notes the role of originality in art:

C'est ainsi que bâille d'avance d'ennui un lettré à qui on parle d'un nouveau «beau livre», parce qu'il imagine une sorte de composé de tous les beau livre's qu'il a lus, tandis qu'un beau livre est particulier, imprévisible, et n'est pas pas faite de la somme de tous les chefs-d'ouevre précédents, mais de quelque chose que s'être parfaitment assimilé cette somme ne suffit nullement à faire trouver, car c'est justement en dehors d'elle.

So it is that a literate person yawns in advance when one tells him of a “good book,” since he imagines a sort of composite of all the good books he has read, while a good book is individual, unforeseeable, not at all made as a sum of all the previous masterpieces, but something that cannot be unearthed in that totality, rather, precisely something outside of it.

... la volonté... est aussi invariable que l'intelligence et la sensibilité sont changeantes, mais, comme elle est silencieuse, ne donne pas ses raisons, elle semble presque inexistante; c'est sa ferme détermination que suivent les autres parties de notre moi, mais sans l'apercervoir, tandis qu'elles distinguent nettement leur propres incertitudes.

I read this around 1995, from the date of a receipt inside it. I thought highly of Yourcenar at the time, but found Hadrien a bit lofty and abstruse at that time. It is, as I recollect, about Hadrien looking back at his life, wondering about much of the dreams, empire and glory.

Twenty-some years later, my feelings about it indeed are different. It is a fascinating set of reflections of maturity, of a man conscious of his mortality, thoroughly aware of his own limitations and those of the society surrounding him. He ponders how he can truly improve the welfare of the state, rather than how to increase his own power or win military battles. – It is indeed a very lofty (in a good way) and striking book, certainly an adult one.

Aimé Césaire was a francophone writer and figure, noted as one of the founders of the Négritude movement. He promoted a Pan-African identity among blacks worldwide, rather than following the ideals and traditions of France. He was from Martinique, writing the Retour when he returned from Paris to visit his homeland.

It makes sense to me that descendants of Africans could find a common identity, even when spread around the world. That is like Jewish identity, in a way, with the diaspora much more recent, but without an element of religion. It would really make sense if the identity were found in the old world, or shared in the multiple new worlds, rather than being of Martinique alone.

Ni à la impératrice Joséphine des Français rêvant très haut au-dessus de la négraille.

…

Je viendrais à ce pays mien et je lui dirais : «Embrassez-moi sans crainte… Et si je ne sais que parler, c'est pour vous que je parlerai.»

Neither to the Empress Josephine, dreaming high beyond Negroes.

…

I will come to that country of mine and I will say to it, embrace me without fear. If I don't know how to do anything but speak, it is for you that I am speaking.

I am very glad that I decided to read this work, though the questions of identity it raises are not mine.

I've re-read this short gem, one of my favorites and one of my mother's top dozen books.

It is an intense internal story. The Princess of Clèves, following her marriage to a man she respects but doesn't feel passionate about, finds herself drawn to a courtly suitor.

Je suis vaincue et surmontée par un inclination qui m'entraîne malgré moi. Toutes mes résolutions sont inutiles; je pensai hier tout ce que je pense aujourd'hui et je fais aujourd'hui tout le contraire de ce que je résolus hier.

I am conquered and overcome by an attraction that draws me in spite of myself. All of my resolutions are useless; I thought yesterday everything that I think today and I do today just the opposite of what I decided yesterday.

The Princesse resists the suitor's efforts, but not before they become visible and commented upon in court. Her husband mistakenly believes that she has succumbed, takes ill, and dies, despite ultimately recognizing his wife's innocence. She is then free to marry the suitor, but does not because his character would not make him a good match.

The story initially is one of the Princess preserving her virtue, well told but hardly unusual. The twist that she does not gratify her own passion once she has a legitimate chance is off of the beaten track, a strong resolution evincing the internal strength of her character.

Montaigne was one of the mysterious writers included in the Britannica Great Books of the Western World, a ponderous presence on library shelves in my grade school days. The collection is often criticized, either on the grounds that it is impossible to make any sensible selection from the countless possibilities, or that the editors made the wrong selections, or that the art and knowledge of the West are only drops in a much more meaningful bucket. Be that as it may, Montaigne is included and has had much influence on others later in the canon.

He was also heavily influenced by writers early in the canon. In a way, this is curious, because Montaigne's thought is nothing if not questioning. He himself, in the noted essay De la institution des enfants (On the Education of Children), rails against rote learning, in particular of ancient languages and lore. Yet he continually cites passages from the Greek and Latin classics to illustrate and support his own points.

At any rate, he is very good. Montaigne is an original thinker, always ready to question, not for the sake of being contentious, but for the sake of understanding. He is an adult's writer, so looking back I am not surprised that in grade school I could make nothing of him.

A sample on knowledge from current reading follows:

Et qu'il n'y point de plus notable folie au monde, que de les ramener à la mesure de notre capacité et suffisance. Si nous appelons monstres ou miracles, ce où notre raison ne peut aller, combien s'en présent-t-il continuellment à notre vue? Considérons au travers de que nuages, et comment à tâtons on nous mène à la connaisance de la plupart des choses qui nous sont entre mains: certes nous trouverons que c'est plutôt accoutumance, que science, qui nous en ôte l'étrangeté: et que ces choses-là, si elles nous étaient presentées de nouveau, nous les trouverions autant ou plus incroyables qu'aucunes autres. Celui qui n'avait jamais vu de rivière, à la première qu'il en recontra, il pensa que ce fût l'Ocean: et les choses qui sont à notre connaisance les plus grandes, nous les jugeons être les extrêmes que nature fasse en ce genre.

And there is no more remarkable folly in the world than to bring them back within the bounds of our capacity and sufficiency. If we call prodigies or miracles things that our reason can't reach, how many of them will continually be crossing our horizons? Consider through what clouds, by what groping we are brought to the knowledge of things that are in our hands. Surely we will find that it is familiarity, rather than science, that takes away their strangeness, and that if such things were presented to us newly, we would find them as unbelievable, or more so, than any others. A person who has never seen a river, at the first time he encounters one, will think that it is the ocean. And the things that are the grandest to our understanding, we will rate as the most extreme entities of the kind that nature has ever made.

I started reading the Essais two and a half years ago, when I spent hours with my mother in the last phase of her life. Montaigne certainly does rank as of one of the great figures of Western literature, in my belief. His style is deeply penetrating though wandering. He questions everything, ending up believing in our human nature and in the thinking of the early Greek and Roman philosphers.

Le Clézio is a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, as well as awards from the Academie Francaise and other prestigious groups.

Le Clézio is a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, as well as awards from the Academie Francaise and other prestigious groups. In this age of misery-drenched writing, his work is remarkable for its fundamental optimism, its ability to find joy and love of our world and immediate neighbors, amid the recognition of sadder parts of life. His style is approachable as well. I am very glad that I opened these two works, and I expect that I will read others.

In this age of misery-drenched writing, his work is remarkable for its fundamental optimism, its ability to find joy and love of our world and immediate neighbors, amid the recognition of sadder parts of life. His style is approachable as well. I am very glad that I opened these two works, and I expect that I will read others.

Ce qu'il éprouva en ce moment échappe à la langue humaine.

C'était Elle.

Quiconque a aimé sait tous les sens rayonnant que contiennent les quatre letters de ce mot: Elle.

What he felt at that moment is beyond human language.Victor Hugo, Les Miserables

It was She.

Whoever has loved understands all the radiant feelings that those three letter of the word engender: She.

© 2026 Paul Nordberg